Review

‘Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers,’ by Rebecca McCarthy; (University of Washington Press, hardcover $29.95)

A biography about one of Montana’s most well-known writers and easily its most famous fly-fishing author is likely to be a popular one among the set that comes to this state to fish the now extraordinarily busy Blackfoot River. It is likely to also be liable to be picked up by the people who have lived in Missoula and still think of it as a “writer’s town.” But Norman Maclean is a wily old devil, and Rebecca McCarthy’s “Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers” makes that slipperiness and devilishness more accessible, if perhaps not perfectly understandable.

People are also reading…

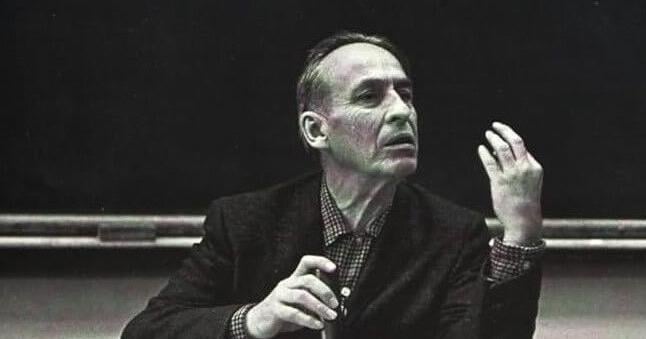

Any review of this new biography, published by a former Atlanta Journal-Constitution journalist and former student and family friend of Maclean, is going to have to contend with the fact Maclean wrote the most famous book in Montana’s literary canon. “The little blue book” or “A River Runs Through It and Other Stories,” was a work of pained labor by a man who had picked up a pen to write fiction in his youth and then didn’t touch the form again for a half-century. McCarthy’s book doesn’t go through all the twists and turns of his writing process, or of the honing of his storytelling skills over the decades, but rather deals with the daily engagement of a professor with his students and of McCarthy’s friendship with a crotchety, curmudgeonly old man who was both capable of extending deep and serious friendship to students, professors, and old foresters alike, but was viciously judgmental and unforgiving if he believed people had failed him.

Maclean was a bit of a bastard, and McCarthy has felt his wintry chill in her own life. Maclean convinced the small-town Southerner and aspiring writer to come to the University of Chicago, where he had taught for several decades as an English teacher and neo-Aristotelian scholar. (Except the man only ever published but a handful of academic articles throughout his career, a strange but understandable tic that most likely came from having a father who forced him to write composition after composition that he then edited down into nothing and threw into the wastebasket each day.) The two of them had a friendship made up of long walks, tea spiked with whiskey, crockpot meals, and conversation. But as McCarthy moved into her mid-20s, she and Maclean had a falling-out that is never fully fleshed out in the biography, but he says something remarkably cruel about McCarthy to one of his friends:

“I learned that in 1980 he had written to a friend who was recovering from surgery that after a visit from me, he himself had been disabled, ‘engaged in what her friends refer to as ‘Recovery from Rebecca.’ I’ll trade her to you for an infected kidney.’ ”

“Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers,” by Rebecca McCarthy

It certainly tracks that Norman and his brother would have left a dumb city slicker to sunburn himself to kingdom come after reading that bit of prose.

It is that cruelty, and McCarthy’s diligent discovery of what exactly in “A River Runs Through It” is fiction, that offers what is probably most interesting to readers of a book about the famous author of the most famous fly-fishing story around. While this biography is not an exegesis of the “the little blue book,” it does give good details about what in was real, and why Paul’s death in Chicago was never going to be written about as it was in life. Maclean was worried about his family’s reputation, but also was grieving his brother’s three decade-old demise as he was putting his wondrous shadow casting skills on the page. Combinations of places, times, trips, and finally, his brother’s passing mean that this was not nearly as close to real-life as the story itself might want to be. Instead, it becomes a story, a story that is more alive for what it won’t recover and will never die, because it is haunted by waters.

Thomas Plank is a former Missoulian and Independent Record journalist. When he is not working for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, he is fly-fishing western Montana’s rivers and considering better ways to expand his bookcase situation because let him tell you, he’s running out of room already.