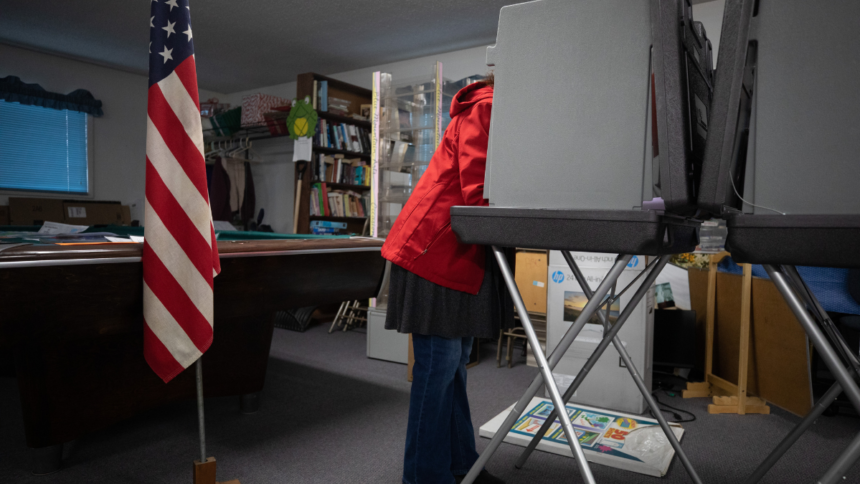

More than a dozen trained volunteers fanned out across 19 of Missoula County’s 22 polling stations on June 4, fixing their eyes not on the results of inter-party primary battles but on the election process itself. Their presence constituted the trial run of the Montana Election Observation Initiative, a new effort by a pair of former political heavyweights in Montana’s election integrity debate to combat misinformation with firsthand nonpartisan insight.

“We want to provide a process and a report and generate data that folks can trust and have faith in,” said former Montana Commissioner of Political Practices Jeff Mangan, who co-chairs the initiative alongside former Republican state lawmaker Geraldine Custer.

The results of the group’s Missoula County test, documented in an eight-page report released this week, concluded that the primary election was “generally well-conducted” by local officials and election workers. Now Mangan and Custer are quickly turning their attention to recruiting and training more than 100 additional observers in communities throughout the state, with the goal of conducting similar work in as many as 15 counties during November’s general election.

In Montana and nationally, the security and integrity of the electoral process came under intense political fire following the 2020 presidential election. Former President Donald Trump’s allegations of widespread voter fraud that year — which have been repeatedly rebuked by experts — found enduring traction among his most ardent supporters, fueling a wave of stricter regulatory proposals in state legislatures, as well as ongoing criticism of established election administration procedures and infrastructure. Concern over a resulting erosion of voter faith has inspired some elected officials and organizations to counter such activity with initiatives to bolster confidence in America’s democracy.

One such voice is the Carter Center, a global nonprofit founded by former President Jimmy Carter that has for decades monitored democratic elections in dozens of countries, including Lebanon, Zimbabwe, Nepal, Myanmar, and Nicaragua. In recent years, the center has expressed increased interest in applying that expertise in the United States, dispatching nonpartisan election observers to Fulton County, Georgia, during the 2022 midterm election and supporting local observation efforts in Michigan and Arizona.

Mangan credited the Montana Election Observation Initiative’s formation in large part to the Carter Center, noting that he first discussed the undertaking with one of the nonprofit’s consultants last year. The Carter Center is the primary partner in Mangan and Custer’s work and provided the funding necessary to pay volunteer observers the $200 honorarium they received during this month’s trial run.

RELATED

Trust, perception and Montana elections

Heading into the 2023 session, Montana was primed for a pitched policy debate over the integrity and security of its election process. Now the conversation among lawmakers has kicked loose questions about trust, perception and how extensive the case for change truly is.

“I wholeheartedly endorsed them coming to Montana, just based on my last two years as commissioner trying to unring the bell of election disinformation and wanting to make sure people had the facts when examining election integrity and what’s happening at the polls,” Mangan said. “This seemed like a natural way to continue as a civilian, as a citizen of Montana.”

Mangan added that neither he nor Custer are receiving payment for their roles as co-chairs, though the two did participate in the observations at two Missoula County polling locations.

The report produced from last week’s observations concluded that Missoula voters could “take pride in a well-administered in-person voting process.” But observers, who were trained in the various laws, regulations, and procedures pertinent to elections, did note several specific areas for improvement. Among them were inconsistencies in the instructions about Election Day voter registration given at the polls by election judges and a lack of privacy screens for voters casting ballots at one polling location, none of which, Mangan said, were significant enough to affect the results of Missoula’s primary.

Missoula County Elections Administrator Bradley Seaman, who has facilitated multiple public tours of various pre- and post-election processes, said he welcomed the opportunity to field such feedback.

“It’s critical that we have people come and see this, and the idea of reporting out on it, too, is fantastic,” Seaman said. “Data-driven, accurate reports that show reasoning as to where, why and what might be doing well or need improvement means a lot compared to just a glossy report that doesn’t have data you can use to help follow up.”

As they expand their observations this fall, Mangan and Custer said they’re mindful of the initiative’s impacts. Mangan noted a desire to select counties that will represent the urban, rural, and Indigenous diversity of Montana’s voting communities. And, since local election offices themselves rely on engaged citizens to help staff the polls, both acknowledged a need to avoid competing with those offices for volunteers.

Having overseen elections as Rosebud County’s clerk and recorder for more than four decades, Custer is well-versed in such details. She attributed her participation in the initiative to the same “fire” that prompted her, during the 2021 Legislature, to go against her party and oppose several election-related bills, including a hefty revision of voter identification requirements. Custer’s primary hope, she said, is that nonpartisan observations can give voters confidence that Montana’s elections are fair, accurate, and by the book.

“I’m just hoping that we have faith in our elections,” Custer said, “that we show that we are doing things by the law, by the rule, and that pretty much across the board in Montana, we’re doing things to the best of our ability to make sure that everything is done just right.”