The rivets were still popping from the seams of the St. Mary siphon when Jennifer Patrick started crunching the numbers for repairing the century-old system that 18,000 residents of Montana’s Hi-Line depend on for water.

It would take 3,600 feet of pipe — two-thirds of a mile of pipe so big men can walk through it without bumping their heads — to get water flowing again to a 200-mile stretch of the Milk River Irrigation Project. They would need a new steel bridge across the St. Mary River and enough earth-moving equipment to restore a river channel completely buried beneath rocky soil eroded from the hillside where the siphon blew.

They were short of the one thing money couldn’t buy: time. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation broke the news Tuesday that for the first time in a century, the Hi-Line will be without water from the St. Mary River for more than a year, reports the Montana Free Press.

Community water towers and reservoirs along the route will have to rely on runoff for recharge at least until August 2025, assuming everything goes right. Runoff isn’t much in an area that gets less than 12 inches of precipitation a year and can go “open” in the wintertime, meaning there’s no snow accumulation.

Map by Eric Dietrich/MTFP

“There’s a lot of things that are going to have to fall perfectly into place, but we’re moving forward,” Patrick told Montana Free Press, noting that replacement pipe might not be available for another six months.

In August, Fresno Reservoir, a key source of stored water for the area, will be drawn down for repairs and won’t be able to fully recharge until the siphon work is completed, sometime next September at the earliest.

“If we have an open winter, construction on Fresno, and the lack of supply from [Lake] Sherburne, by next year it could be tough to get a cup of coffee or flush the toilet in Havre, Harlem, Chinook …” said Marko Manoukian, a member of the irrigation project’s joint board of control for more than 20 years.

The siphons have been a “dripping time bomb” for decades, Manoukian said, borrowing a phrase used by a magazine article that brought national attention to the project a few years ago.

THE MONEY SPIGOT

The St. Mary Siphon is one of several mega projects authorized by Congress in 1905 to spark agriculture growth in the West. The objective was to divert water from the Canada-bound St. Mary River near Glacier National Park to boost the anemic flow of the Milk River, which was known to run dry six out of 10 years, according to the Milk River Joint Board of Control. The diversion, with the turn of a valve, kept the Milk watered all the way to the Missouri River, more than 700 meandering river miles downstream.

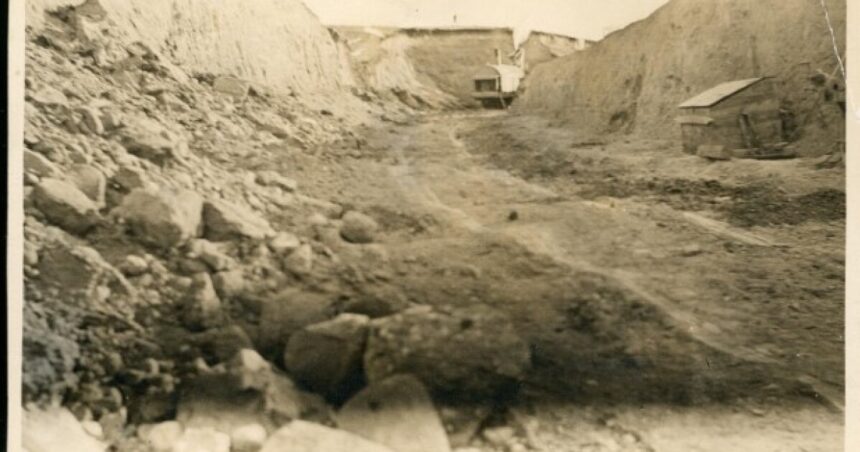

Using only gravity and natural suction, a series of pipes and canals drew water uphill from the St. Mary diversion dam and then down to the North Fork of the Milk through a series of drops that managed the flow as the water reached the Milk River Irrigation Project. Yellowing photos of the project’s creation show workers digging channels by hand, with some work employing horses and wagons.

Locals consider the project an engineering marvel with a congressional Achilles’ heel that’s left big-ticket maintenance issues unaddressed until catastrophic failure forces action. A 74%-26% cost-sharing agreement, with local communities expected to pick up the largest share, has been a federal funding requirement for decades. That’s because Congress, not long after creating the Bureau of Reclamation and directing the agency to irrigate the West, grew concerned about how much federal money was being spent on the projects. Lawmakers began shifting the costs to water users and extending repayment terms from 10 years to 40. The assumption, as laid out by the Congressional Review Service in 2020, was that irrigation fees and the electricity generated and sold via the projects could cover the costs of maintaining them. For big-ticket expenses, the expectation is that local money be provided up front.

“You know 75% on hay crops doesn’t pencil out on a $70 million project,” Patrick said, referring to the region’s primary irrigated crop and the estimated bill for repairing the siphons.

Hay isn’t a big moneymaker, but hay that’s raised along the not-quite-mile-wide ribbon of green hugging the canals and banks of the Milk River feeds into the cattle operations on the outlying dry prairie. Without hay for feed, it takes more than 10 acres to support a single cow and calf on those operations.

“We’re kind of stuck with some really horrible congressional authorization,” Patrick said.

Montana Historical Society Photo Archives. Credit: Photographer unidentified. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Montana Dams and Irrigation Collection / Montana Historical Society

It’s estimated that the cost of repairing every element of the system would be about $400 million, which amounts to about $3,305 for each of the 121,000 acres irrigated by the project.

Crisis changes the conversation about payment.

“We could get into farm policy of the last 100 years and you could write a fricking book about that. The truth is it doesn’t work,” said U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, who dryland farms not far from Havre, the largest of the Hi-Line communities dependent on the Milk River for irrigation and drinking water. “And the only way to get it relieved is you got to do a series of studies, which by the way for the most part have been done on this project and found they couldn’t support 75%.”

Tester, Montana’s only statewide elected Democrat, carried the Fort Belknap Water Compact and Settlement bill through the Senate in June. There is $275 million for the Milk River Project tucked inside the legislation, which settles water rights claims of the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine tribes of the Fort Belknap Reservation.

Courtesy Milk River Joint Board of Control

Every federal water project on the Hi-Line is connected to a federal obligation to honor tribal treaties, from Fort Peck to the Rocky Boy’s reservation. Those treaty obligations have been used as an end-around to federal cost-sharing requirements for decades.

The House version of the Fort Belknap compact is being carried by Western District U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke, a Republican.

“Let’s get the engineering done. Let’s get the parts ordered, then move forward and fix the St. Mary’s bypass so we don’t have the discussion 20 years from now,” Zinke told MTFP. The project should be more than a regional concern, Zinke said, because the rivers involved are at the upstream limits of two major drainages: Hudson Bay for the St. Mary, and the Missouri River for the Milk.

There is some anxiety among project stakeholders about differences between the Senate and House versions of the Fort Belknap legislation. The House version includes $250 million for a Blackfeet Reservation wastewater treatment plant, which the Senate version doesn’t. If both pass, the two versions of the bill will have to be reconciled in conference committee, where members from each legislative branch hammer out the bills’ differences. There aren’t many working days left in the federal funding year, which ends Sept. 30. Lawmakers are in D.C. for only 8 days through the end of August. The Congress’ September schedule, usually dominated by a budget scramble to keep the federal government from shutting down, hasn’t yet been published.

Funding for the project has been flowing steadily, by congressional standards, for five years, mostly because of infrastructure failures. In May 2020, when one of the chutes diverting water to the Milk washed out, Congress approved $8 million, which was just a down payment for the necessary expenditures. The project was shut down 22 weeks for repairs.

In 2021 the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill was passed with $100 million included for the Milk River project. Tester, who had a role in crafting it, was the only member of Montana’s federal delegation to vote for the infrastructure bill.

In 2022, another $85 million was allocated to St. Mary diversion and headworks replacement, followed by the $275 million in the Fort Belknap Water Rights Settlement.

But the money flowing to the Milk River project during crisis points isn’t indicative of the work taking place, said Ryan Newman, manager of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Montana area office.

“On the surface, it looks like we’re running things to failure and then have an emergency upon failure, when in reality that’s not the case at all,” Newman said. “There’s two different things going on. First off, the entire system is very old, showing its age, and reaching the end of its functional service life up and down the system.

“There’s an incredible amount of repairs, replacements, rehabilitation that takes place annually up and down the entire system. There are a couple of very large features that come with a very large price tag. And those are the items that we’re seeing,” Newman said.