SEATTLE — In September, a social-media account called “Is EA Sports College Football Out” began periodically posting one word:

Days passed, and the “Nos” piled up. No. No. No. No. No. But for dedicated college football fans, the wait was even longer.

Before this week, Electronic Arts’ most recent college football video game — “NCAA Football 14” — had been released on July 9, 2013. The series was then waylaid by legal disputes surrounding player likenesses, pitched into an 11-year purgatory while the sport painstakingly evolved.

Of course, college athletes were finally permitted to be paid for utilizing their name, image, and likeness (NIL) in 2021, which allowed EA to compensate the players it profits from. (Players who opted in received $600 … and, of course, a copy of the game.)

People are also reading…

At precisely 1 p.m. Monday, the “Is EA Sports College Football Out” account posted one more word.

“For a lot of people, this is a holiday,” Ryan S. Clark, a devotee of the series and NHL writer for ESPN.com, told The Seattle Times on Monday.

It’s a holiday steeped in nostalgia — in midsummer marathons on prehistoric PlayStations, in triple-option offenses and players lost to time, in critical recruiting battles for fictional five-star safeties, in regional conferences (remember them?) and in-state rivalries.

“NCAA Football 14” had 20 predecessors, dating to “Bill Walsh College Football” in 1993. It also had a frenzied following, a generation of football fans who developed dynasties — chiseling national champions out … of small-school Cinderellas.

“For me, it was really cool because I got to see really good teams and players that in 1998, in Minneapolis, I wasn’t ever going to see play until the bowl game,” said Dave Southorn, 42, who later covered Boise State football for The Idaho Statesman and The Athletic. “You got this really good view of the college football landscape through that game.

“That really helped me, to be frank, as I was figuring out what I wanted to do with my life. I was like, ‘Oh, this is cool.’ I knew things that others didn’t. Everyone was talking about Michigan or whoever. I was like, ‘Have you heard of Tulane?’ “

Clark, likewise, celebrated the annual summer release with a weeklong marathon, as he and a friend staged a sport-wide tournament (modeled after the UEFA Champions League in European soccer) to establish supremacy.

“We did our own statistical tracking [of games],” said Clark, 39, who traces the tournament to his high-school years in Florida from 1998 to 2002. “We were absolute nerds about it, and we totally own it. We absolutely own it.”

Concluded Clark, who lives in Seattle: “This is what we would do from 4 o’clock in the afternoon to 2 o’clock in the morning every day for a week.”

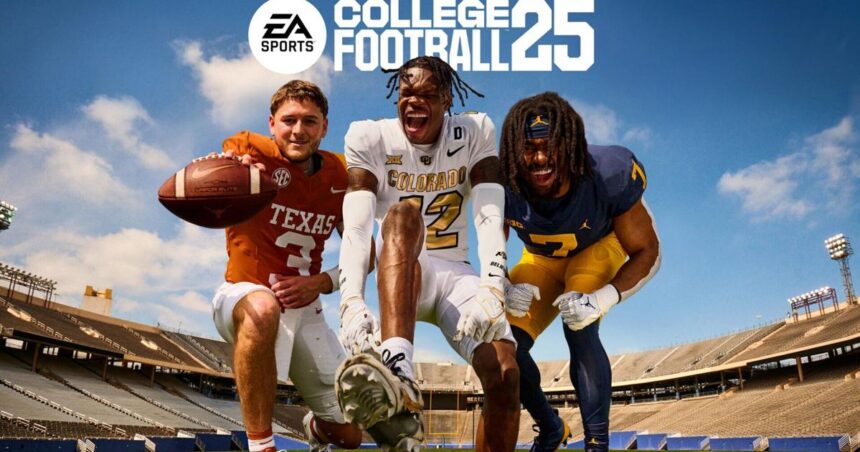

Decades later, the arrival of “EA Sports College Football 25” has attracted a similar response, flooding social-media feeds with flea flickers and stadium shots and shaking student sections. As 247Sports college football reporter and podcaster Bud Elliott posted Tuesday on X: “The EA Sports College Football release has completely upstaged media days buzz. Search trends [online] are wild. To the point where talking college football on a college football show instead of talking about the video game is legit bad business.”

The business of college football is also reflected in the game, as players must maneuver NIL deals and the transfer portal to retain top talent. An athlete’s academics, leadership skills, health, training, and brand all must be monitored.

Indeed, a whole lot happened in the 4,025 days between the releases of “NCAA Football 14” and “EA Sports College Football 25.”

For the sport, the franchise … and its fans.

“The last time this game came out, I wasn’t yet engaged,” Southorn said. “I’ve been married for nine years now. That’s how long it’s been for me.”

Joked Clark on Monday morning, in a similar situation: “When 1 o’clock rolls around, my wife understands that it was a great run for our marriage. We had a lot of great years. We put championships in the rafters. But I’m a ghost to her now, and she knows that, God bless her.”

Southorn may soon count among the game-playing ghosts. The University of Colorado alum, who now handles content and communications for a hospital system in Idaho, requested off work Friday to reignite a former flame.

“Daycare is going to come in clutch,” said the 42-year-old father and Carnation native. “I’ll get up, take [daughter Kennedy] to daycare in the morning. Maybe I’ll swing by the doughnut shop and grab something, and then just settle in. I’ll probably order a pizza or something at lunch because I don’t want to move.

“I know I’m in a boat with a whole lot of people. When you get to 40ish and you’ve got kids, you don’t have as much time. But I know I’m literally going to find ways to make time. Because we all need something.”

This game, for some, is more than a silly aside — or a time machine to a tournament lasting until 2 a.m. It’s not just nostalgia wrapped in new graphics and updated uniforms.

It’s also a referendum on college football’s deepening divide, on the parity diluted by super conferences and media-rights money. It’s an individual objection — a place where Army and Akron and Appalachian State can overwhelm Alabama, where Washington State can pummel its former Pac-12 partners into apologetic pieces.

It’s a place where former Notre Dame and Wake Forest quarterback Sam Hartman — whose Demon Deacons never defeated Clemson in his five seasons as the starter — can topple the Tigers, 105-34, as they did Tuesday.

“Just blowing off some steam…” Hartman posted, along with a screen shot, on social media.

It’s a place where anything is still possible, provided you can play.

“I think maybe in the back of our lizard brains, you have some control over it now. You can make the Cinderella story happen,” Southorn said. “You can build someone up, where realistically it probably wouldn’t happen [in the current era of college football] because of NIL and conference affiliation. You can return it to the way it used to be and feel like college football is a little more even or fair. I think that’s a big part of it.”