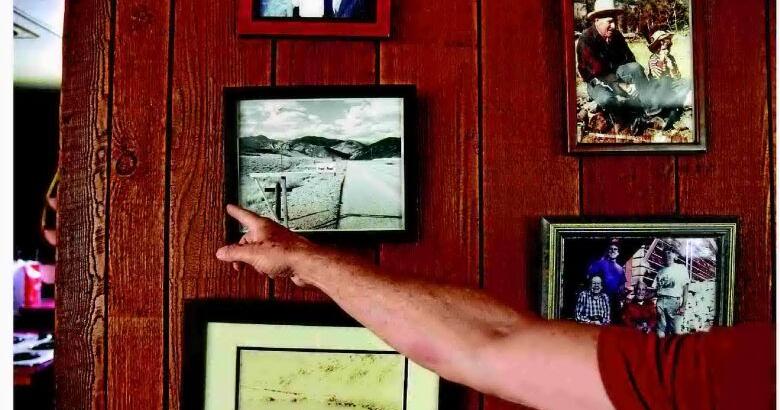

Erich Pessl’s roots run deep in the Gallatin Canyon.

Although he wasn’t born on the land, it has been in his family since 1959. That year, his grandfather, Freddie Pessl, visited southern Montana from Michigan, seeking a retirement spot in the mountains.

Directed to the property, Pessl skied up what is now Beaver Creek Road and discovered the original homestead cabin built in 1904. After exploring the lush land filled with Douglas firs, spruce and aspen trees, Pessl returned to the highway and immediately closed the deal.

In the more than 60 years since Pessl purchased the 170 acres of land, it has become a cherished home for multiple generations. Younger family members have visited during summers, and Erich Pessl eventually raised his children on the land.

“Our family was interested in keeping our grandparent’s land close to its original state for future generations,” Pessl said.

People are also reading…

For families with ancestry in Gallatin County, the sight of sprawling hayfields and lush pastures gradually transforming into concrete parking lots and luxury housing has become all too common as the city’s population continues to flourish.

It’s a familiar story: as land prices climb and developers move in, farmers and landowners often feel compelled to sell, viewing it as their sole path to financial security despite their memories and deep attachment to the land.

However, for Pessl and other landowners, county farmers and ranchers, their stories no longer have to end with relinquishing the land they love.

Across the country, conservation easements are becoming increasingly popular tools for maintaining agricultural land, providing wildlife habitat and preserving open space.

“Montana land and the agriculture that happens here doesn’t produce a ton of profit per acre,” said Kelsey Larson, an MIT Ph.D. candidate studying the role of conservation easement tax incentives. “If you’re a farmer who is thinking about what do I want to do with my life…it’s pretty understandable that some farmers and ranchers would say, you know, I might get out of the business use of money to do something else.”

Despite farmers and ranchers playing a pivotal role in local and national food production and providing economic stability across Montana, the average farmer salary in the state is $46,000, as per the 2022 census of Agriculture Data.

The average cost of running a farm in the U.S. was $226,986 in 2022, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, marking a 15.25% increase from $196,087 in 2021.

Built upon the ideology that open spaces and farmland should remain intact, the Gallatin Valley Land Trust embarked on its mission to conserve land cherished by both longtime residents and newcomers for centuries.

Founded in 1990 by Chris Boyd, the nonprofit Gallatin Valley Land Trust has conserved 67,514 acres acres of land in the Gallatin Valley and surrounding communities through partnerships with private landowners and voluntary conservation agreements.

These agreements, known as easements, are consensual arrangements between landowners and land trusts like GVLT. By entering an easement, the landowner agrees to donate development rights to GVLT, ensuring the property remains undeveloped and preserving its natural state for future generations.

In 2007, the Pessl family finalized a conservation easement with GVLT, preserving over 170 acres of land.

“We often, while we’re on their property, sit back in amazement to consider that if we didn’t put a conservation easement on the property, there would likely be dozens of homes on the conserved land. It just wouldn’t be the same as it is now,” Pessl said.

Even if the land is sold, the easement remains in place. Due to restrictions on development, the land may lose value; however, the landowner is typically compensated for this loss through financial compensation or tax credits.

Since 2000, the voter-approved Gallatin County Open Lands Program has compensated landowners, including farmers and ranchers, for the lost development value, making it financially feasible to conserve properties that might otherwise be sold.

Since its inception, the Lands Program has conserved over 50,000 acres, equivalent to 78 square miles — more than three times the size of Bozeman. The program’s bond funding also secures matching funds from government conservation easement programs, leveraging taxpayer dollars at a five-to-one ratio, according to GVLT.

Landowners who participate in easements receive immediate and long-term tax benefits. These include claiming the easement as a charitable deduction on federal taxes and reducing estate taxes, according to Larson, the Ph.D. candidate.

GVLT’s conservation easement efforts were significantly influenced by the rapid development encroaching upon Gallatin County, according to EJ Porth, the nonprofit’s associate director.

Since 1990, Gallatin County has experienced significant development, with 15% of all Montana homes built here. According to a Headwaters Economics report, between 1990 and 2016, over 43,000 acres — equivalent to 146 square miles — were converted from open space to residential development. Additionally, from 2001 to 2016, the county’s population grew three times faster than the rest of the state.

According to the report, this growth has contributed to more than one-quarter of all new jobs in Montana and has benefited all sectors of the economy except farming. However, it has also led to the loss of a substantial amount of the county’s open space.

“In the first 30 years that GVLT was around, we were successful in protecting about 50,000 acres, but more than 100,000 acres in Gallatin County alone were converted for residential subdivisions. That translates in my mind to developers working twice as fast as conservationists, right? That was really hard for us to hear,” said Chet Work, executive director at GVLT.

Still, in 2021, Gallatin County had over 130,000 acres in conservation easements, equating to over 200 miles, according to a state government report.

Currently, GVLT is executing a five-year strategic plan to triple its land conservation efforts, aiming to protect 25,000 acres by 2028, according to Work. Since 2023, the nonprofit has conserved 13,309 acres.

“We’re on pace, literally to do that,” he said.

Work said that one of the big gest challenges the land trust faces is its relative newness and uncertainty about whether future landowners will maintain the easements.

“We don’t have easements that are older than than 33 years. So we haven’t seen a lot of properties being with third or fourth owner,” he said. “But I think the further you get away from those landowners with the original intention and original conservation values, the harder it is for us to ensure that the primary owners wishes are maintained.”

Some critics argue that conservation easements do not guarantee public access to activities like hunting and hiking, despite public funds being used to support these easements.

Others like George Wuerthner, the former ecological projects director for the Foundation for Deep Ecology, argue that the public shouldn’t help pay for private enterprise at all.

“If there’s public money being used, I often feel like it would be better off to get an outright purchase, where the public can utilize the land,” he said.

Wuerthner also criticized land trusts for seeking to preserve waterways and wildlife habitats while supporting conservation easements on agricultural lands like wheat fields.