Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week’s contribution is from Michael Poland, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey and scientist-in-charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

(Editor’s note: In an almost prescient fashion, Michael Poland wrote this week’s column before the eruption at Black Diamond Pool in the Biscuit Basin on July 23.)

An underappreciated geologic hazard in Yellowstone National Park is that of hydrothermal explosions. These are not volcanic eruptions, but rather sudden episodes of water flashing to steam underground. Small hydrothermal explosions happen almost annually someplace in Yellowstone National Park — like the 1989 explosion of Porkchop Geyser. Every few thousand years, large ones can also occur. The park is home to the largest-known hydrothermal explosion crater on Earth — Mary Bay, on the north side of Yellowstone Lake, is 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) across and formed about 13,000 years ago.

People are also reading…

Monitoring stations in the Yellowstone region have historically been installed outside thermal areas to avoid the noise caused by all that boiling water moving around beneath the surface — that noise can make it hard to detect small earthquakes and subtle ground deformation. But in response to the need to better monitor hydrothermal hazards, the 2022–2032 Volcano and Earthquake Monitoring Plan for the Yellowstone Caldera System highlighted the importance of installing geophysical monitoring stations in geyser basins. Such monitoring could identify explosions that might otherwise go unnoticed and may even detect precursors that could serve as early warning of an impending hazard. The first such station was installed in Norris Geyser Basin in September 2023.

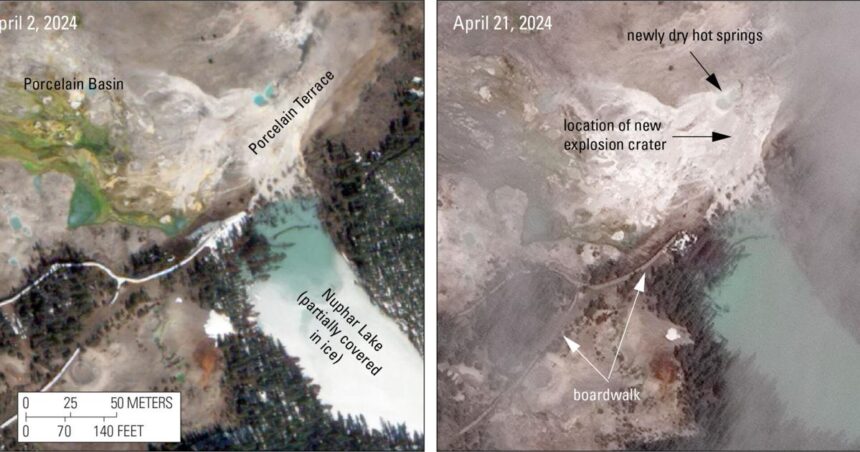

In May 2024, geologists doing field work in Norris Geyser Basin discovered a small crater a few feet (1–2 meters) across that was surrounded by fragments of silica sinter and disrupted ground. The crater was located on Porcelain Terrace, near the western edge of Nuphar Lake and above Porcelain Basin on the east side of Norris Geyser Basin, and it had formed since the last time geologists had visited the area in September 2023. This area had been exceptionally active during the prior two years, with enhanced runoff from thermal features on the terrace flowing into Nuphar Lake, causing the lake level to rise significantly. In May 2024, however, the features in the area were quiet, and no water was being emitted.

An examination of high-resolution satellite data indicated that the thermal features on Porcelain Terrace went from being very active to mostly dormant between April 2 and 21, 2024. The new crater and disrupted ground were too small to be visible in these images, but the timing of changes to the nearby thermal features provided a starting point for examining monitoring data for signs of an explosion.

The new hydrothermal monitoring site at Norris Geyser Basin includes not only GPS and seismic sensors, but also an infrasound array, which can detect the strength and directionality of low-frequency acoustic energy. On April 15, at 2:56 p.m. local time, the station recorded a strong acoustic signal from the direction of the new crater. Seismometers in the region also recorded a signal, but based on their distance from the crater, the signal was moving at the speed of sound, and not at the speed of a seismic wave — evidence that the signal was caused by a surface event and not an earthquake.

There were no obvious immediate precursors to the explosion in monitoring data. It might be that no changes occurred, or perhaps they were too small to be detected by the stations, the closest of which was about 1,640 feet (500 meters) away. But the data that were recorded unequivocally identified the explosion, which is the first time such an event was recognized using geophysical data in Yellowstone National Park. And using this example, it may be possible to design alarms that can detect future similar events at Norris Geyser Basin using the new monitoring station.

The discovery also demonstrates the utility of continued expansion of hydrothermal monitoring in Yellowstone to detect similar events in the future, not only in Norris Geyser Basin but also in other thermal areas.

The recent Norris explosion occurred only about 160 feet (50 meters) from a boardwalk. Fortunately, the explosion was too small to have ejected debris to that distance, and it occurred during a time period when much of Yellowstone National Park was closed to visitors as winter operations transitioned to summer. The event nevertheless emphasizes importance of following park guidelines and staying on boardwalks and designated trails in thermal areas, and also highlights the hazardous nature of even small steam explosions — a hazard that will be increasingly targeted for monitoring and, with advances in our understanding, forecasting by the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in the years to come.