Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, is an immigration status that helps children whose parents crossed into the U.S. illegally get work permits and not live in fear that they will be immediately subject to deportation.

The program, which began under the Obama administration, covers more or less a half million people — often called “dreamers.”

While the current Biden administration has tightened many immigration and border policies, it has worked to help undocumented people and dreamers find pathways to normalized immigration status and citizenship—namely by offering a program to help dreamers married to U.S. citizens.

By every measure Judith Martinez is a Texan and American by culture—except in immigration status. Her parents, seeking a better life, brought her from Mexico, crossing illegally. But she’s hoping that will change.

In June, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to allow undocumented residents married to U.S. citizens and who have lived in the country for at least 10 years to apply for legal residency. Non-citizen children of such couples also could seek legal status.

The biggest impact will be on DACA recipients like Martinez.

“It’s a relief to not have to do an advance parole or waiver and have the risk of being stuck outside of the United States,” she said.

RELATED STORY |

Immigration rights group voices concern over Biden’s expected asylum rule change

Typically DACA recipients have to leave the United States and apply for normalization of status at a U.S. Consulate.

Naimeh Salem is Martinez’ immigration attorney and her boss. She expects a rush of applicants before the presidential election in November.

“They are not going to be forced to go to their consulate to do an interview on a medical exam, they’re going to be able to do it here,” said Salem. “Yes, everybody is excited, but they have a lot of questions. They want to know the ones that already applied for a waiver.”

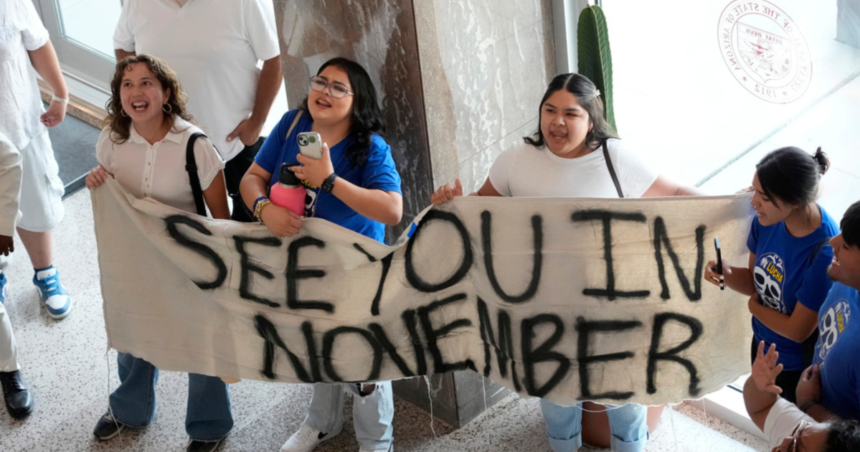

The program could benefit up to a half million DACA holders and the process starts in late August.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick is a legal director for the American Immigration Council.

“Right now, there are hundreds of thousands of people, again, who are eligible, theoretically, to get a green card but haven’t been able to pursue that because of that risk of being separated from their family for a decade,” said Reichlin-Melnick.

RELATED STORY |

Immigration among top issues for voters heading into 2024 election

Immigration policy experts say this is a limited humanitarian shift by a Biden administration seeking to burnish a tougher image on border security through earlier refugee policies that have been some of the toughest in U.S. history.

Those policies have included closing borders to asylum seekers when the numbers top 2,500 a day.

“You have a population of people that is living here, working here in many cases, paying taxes here, has family, are part of their communities, but have no legal way to become a U.S. citizen or even to get some form of permanent legal status that could potentially protect them from deportation,” said Reichlin-Melnick.

DACA holders like Martinez are commonly called “dreamers.” The 28-year-old mother has called Texas home for more than 25 years and says this could be the realization of her American dream.

“We all have different stories, and some stories with them are they haven’t seen their families for more than 25 years,” said Martinez.