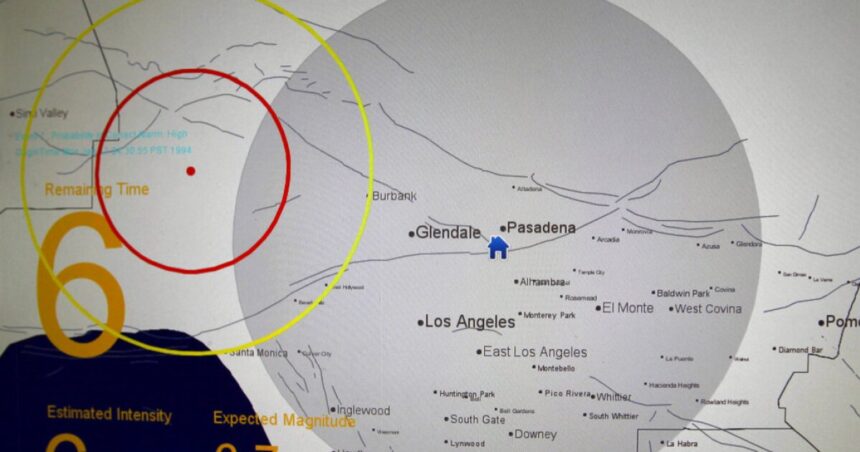

When a 5.2 magnitude earthquake shook parts of southern California Tuesday, residents in the most densely populated parts of the region got an early heads up.

“It’s about a 20-mile radius from where the epicenter of the earthquake was near Lamont when we began having these positive alert times, where people began having some time between when they got an alert and felt shaking,” said Robert de Groot, communication and education coordinator for the U.S. Geological Survey’s ShakeAlert.

ShakeAlert is designed to tell people in earthquake-prone regions when shaking is on the way. The system collects shaking data from stations spread all over the state and sends that information to hubs where it’s compiled. From there it’s forwarded to telecom companies that push notifications to phones, either via the Myshake app or the national Emergency Alert System.

RELATED STORY | Dozens of aftershocks felt after magnitude 5.2 quake shakes California

“Across the board, from detecting the ground motion to getting something into someone’s hands, we’re always trying to shave off even fractions of a second,” de Groot said.

The tech has been around for several years, but on Tuesday in southern California, many residents had — for the first time — enough warning to act before an earthquake hit.

In many ways, it was a banner night for ShakeAlert.

On X, Californians posted their reactions, with one saying they were “impressed that we got 20+ sec of early warning” and another noting the “early warning system… is getting better.”

“It really seemed kinda like time stopped,” Kathy Degner, a Pasadena resident, said of the moment she got the alert. “In how long it felt for me to feel that shaking, that was a long, five seconds is a long time. I think it’s a valuable tool. I think it needs to be worked on. I had friends right near me that didn’t get an alert.”

RELATED STORY | 75% of US at risk for damaging earthquake, new data shows

“The ShakeAlert system is in a constant state of improvement, and so we’re using every earthquake, every opportunity to improve,” de Groot said.

It’s a sign that groundbreaking tech has tangible value and a promising future to protect not just people, but infrastructure.

“How can protecting a system like, say, LA Metro, protecting the train system, benefit [us]? If we were able to let them know that shaking was happening even when it just started, how is that going to impact their ability to move people and stuff after the earthquake is over?” de Groot said.