Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week’s contribution is from Tara Cross, Yellowstone Geology volunteer, and Mara H. Reed, PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley.

Scientists are diligently investigating the hydrothermal explosion that occurred on July 23, 2024, at Black Diamond Pool in Biscuit Basin. An essential aspect of comprehending the recent activity involves delving into past similar events. Past incidents at Biscuit Basin provide valuable insights into the recent occurrences.

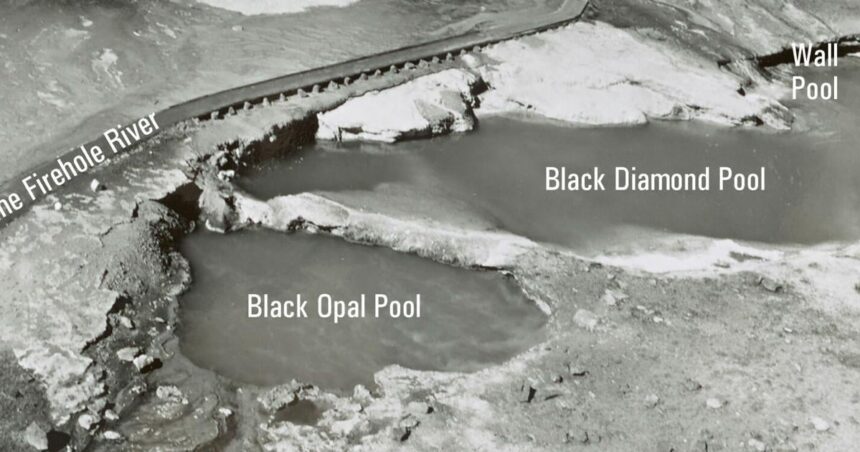

In the early 1900s, Biscuit Basin had a different appearance compared to today. Sapphire Pool still showcased its biscuit-like geyserite formations popularized by F. Jay Haynes’ photography, but Black Diamond Pool did not exist at that time. Historical maps, including those by the U.S. Geological Survey, did not depict any thermal features between Sapphire Pool and the Firehole River. Although the details surrounding the creation of Black Diamond Pool and its neighboring features – Wall Pool and Black Opal Pool – remain limited, evidence suggests that they were a result of explosive events.

People are also reading…

The earliest evidence is a photograph captured by Haynes’ son Jack around 1912, which depicts what is now known as Black Diamond Pool after a hydrothermal explosion that caused the vent to rupture and ejected large rocks from its crater. The exact date of this initial explosive event remains unknown, but the photograph and map dates suggest it occurred between 1902 and 1912.

Records stored in the Yellowstone Heritage and Research Center reveal that additional explosions took place in 1918 and 1925, leading to the enlargement of the crater at Black Diamond Pool and the formation of Wall Pool. Subsequent explosions in 1934 and 1953 created and expanded the crater at Black Opal Pool. Unfortunately, none of these explosions were witnessed, and reports only describe the aftermath: altered pool shapes, significant wash, and newly ejected boulders. For many decades after 1953, no eruptive or explosive activity was reported at any of these pools.

Tracing the history of these events is often complex due to the various names assigned to new features before a standard name is established. Early observers used the name “Black Pearl” for both Wall Pool and Black Opal Pool, causing confusion. By 1959, park geologist George Marler named the easternmost pool “Black Opal Pool” due to its dark opalescent coloration, while collectively referring to the other pools as “Wall Pool” because of the prominent escarpment along their edges. The name “Black Diamond” was introduced by park ranger Frank Childs in the 1930s but gained common usage as the name for the larger of the two Wall Pool features in the mid-2000s.

In early 2006, signs of increased heat flow were observed at Biscuit Basin, with hot ground and new vents emerging between the three pools and the river. This signaled the resurgence of Black Diamond as an explosive feature in July 2006. The first eruption was witnessed by geyser enthusiast Kendall Madsen, who captured a photo showing dark-colored water ejected to a height of 40–50 feet (12–15 meters). Witnesses in close proximity to the pool reported loud thumps accompanying the explosive bursts. Subsequent eruptions occurred at irregular intervals, ranging from two to five days and occasionally as short as five hours. The frequency of events decreased after mid-September 2006, with sporadic eruptions. A few eruptions clustered in late 2011, followed by intervals of weeks or months between eruptions. This phase seemed to conclude by late 2012, with only three eruptions reported before 2024, one each in 2013, 2015, and 2016.

Several of these eruptions over the years were witnessed by visitors, geyser enthusiasts, tour guides, and park rangers. Most eruptions reached heights of 6–20 feet (2–6 meters), lasted 10–20 seconds, and were accompanied by thumping sounds and pops. Eruptions often expelled small rock fragments and mud globules.

In 2009, a group of geologists on a field trip observed an eruption matching the intensity of the first 2006 event, reaching 50 feet (15 meters) in height and hurling rocks in all directions. Geyser enthusiast Bill Warnock witnessed and photographed an eruption in 2011 estimated to be 50 feet (15 meters) high, expelling a significant amount of water towards the river. Some unverified reports from 2006 and 2011 suggest even larger eruptions of 60–100 feet (18–30 meters). Lastly, an eruption in April 2015 projected mud onto the boardwalk and fatally impacted a group of cormorants that were in close proximity.

Except for the hydrothermal explosions that led to its creation, the most recent activity observed at Black Diamond Pool on July 23, 2024, was considerably larger. The historical record raises scientific inquiries that will aid in investigating the 2024 explosion. Questions such as why Black Diamond remained dormant for decades before reactivating as a violent geyser, and why hydrothermal explosions recur in some locations but not others, highlight the significance of studying both past and present events to gain new perspectives on Yellowstone’s prevalent yet often underestimated hazard.