August in Gainesville, Florida, is sweltering. Humidity pushes the heat index into triple digits.

In a field adjacent to the University of Florida campus, Brahman cows huddle in the shade. Snow white egrets hunt in the grass.

The small farm is a classroom — the Beef Teaching Unit housed in the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Florida.

It’s here at UF that Raluca Mateescu, professor of animal genetics and genomics, and her colleagues found that cattle can be genetically tested and bred with larger sweat glands to better tolerate the heat.

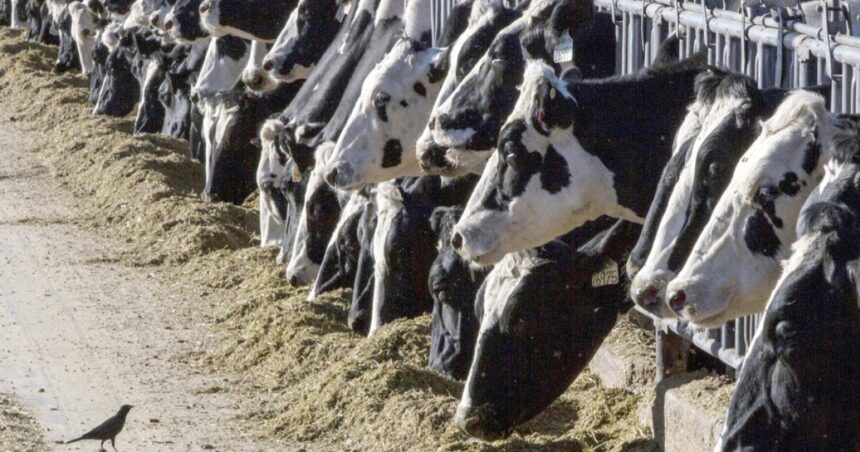

Heat stress is one of the biggest challenges facing the nation’s largest agricultural sector. Heat-stressed cows produce less milk and less meat, and it impacts reproduction. Limiting their activity is one way cattle handle the heat — but 85% of their heat dissipation comes from sweat.

As climate change drives summer temperatures to record levels, more heat-tolerant cows might be the key to a more sustainable food supply.

RELATED STORY | Converting cow manure to fuel is potential climate solution, but critics say communities put at risk

Mateescu and her team examined the sweat glands of nearly 2,500 cows, primarily Brangus, over the last five summers. They took skin biopsies, blood samples and the cattle’s body temperature. They weren’t surprised by the sweating. “But we were surprised by the variation in their skin properties,” Mateescu said.

That variation could be used to select cattle that tolerate heat better. The study was published in June in the Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology.

“There are some things that they can see and they can select for just by looking at the cattle — for example, coat score. A shorter, sleeker hair is going to allow them to survive and do better in a subtropical environment,” Mateescu said. “That’s something a producer can see and select for. But the sweating is not.”

The stakes are high: Half of the cattle in the world live in a subtropical environment. In the United States, 45% live in subtropical conditions. Economic losses due to heat stress add up to $369 million per year globally.

“It also affects their welfare and their health. So there are really big consequences to heat stress,” Mateescu said.

The USDA’s Climate Change Resource Center estimates human-driven climate change will push temperatures up between 2-8 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century.

“That’s going to present a big challenge for us. At the same time, we are still expecting our cattle to produce a lot,” Mateescu said.

The research is particularly important to sixth-generation cattle rancher Jim Strickland.

“We’re like junior geneticists, anybody in the cattle business that’s been in it for a long time has learned something about genetics,” Strickland said.

Strickland’s Black Beard Ranch in Myakka City, like most in Florida, is primarily a cattle-calf operation. He sells calves to other ranchers across the country and around the world. Choosing the right cows matters, especially when designing the next generations.

“I rely on my breeders, the universities and breed organizations to give me the information, the data and the research that I can depend on. So, what does DNA testing mean today? A lot. What’s it going to mean ten years from now? A lot more.”

Genetic testing is already done for milk production, meat quality, and feed efficiency.

“Now we’re doing DNA for animals that are better suited to thrive in hot climates. That’s a game changer. That is an absolute worldwide game changer,” Strickland said.

RELATED STORY |Bird flu is spreading to more farm animals. Are milk and eggs safe?

Cattle ranchers already have ways to mitigate heat. They provide shade, fans, sprinkler systems and trees and water features in the pastures. Strickland’s cattle aren’t heat-stressed, but he wants to do anything he can to keep them comfortable and be more efficient. It will help keep him in business.

Genetic testing for heat isn’t available yet, but Mateescu hopes to have a market-ready test in the next year or two.

“The work that she’s doing there is vitally important,” Strickland said. “And I think it’s the very beginning.”