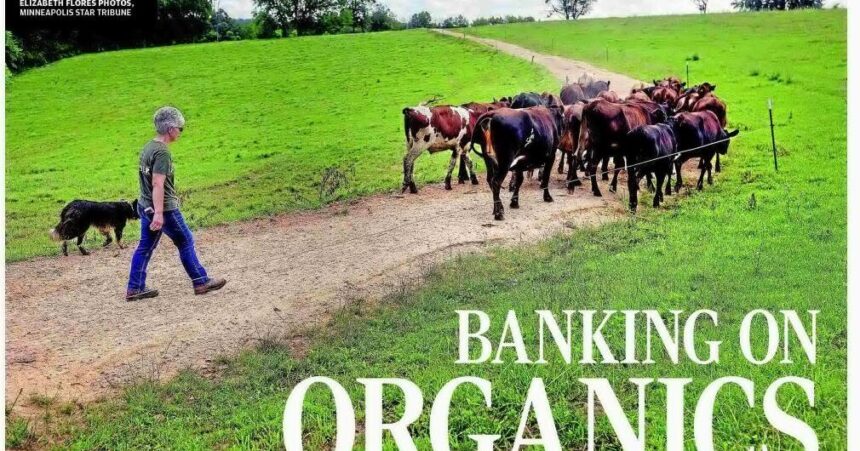

Lisa Hass — in work boots, jeans and a shirt embossed with “FARMER” — hitched a pole beneath a fence wire and lifted it high for dozens of half-ton heifers to amble forward toward greener pastures in the Wisconsin summer sun.

“We call them a rainbow herd,” Hass said, with a chuckle. “We’ve got a mixture of Holsteins, Jersey crosses, Normandy, Dutch Belted.”

Dairying has deep roots in the surrounding dells of the Mississippi River. But storm clouds are gathering above these colorful farms, under threat of going big or going out of business.

For years, many small dairies facing extinction found saving grace in organic milk. But now that industry is also facing headwinds, and many worried observers fear a downturn in family farms will threaten surrounding rural towns, where merchants rely on agricultural operations to buoy local economies.

People are also reading…

Since the early 1970s, 90% of farms across Minnesota and Wisconsin have sold their dairy cattle. The pace hasn’t slowed. Last November, dozens of dairy farmers in Minnesota opted not to renew their milking permits.

For some farmers, the answer to staying open has been organic, where a higher price on milk stabilizes a small farm. An operation certified as organic follows federal rules specifying, among other requirements, that cows eat organic feed, including in pastures free of fertilizer. The payback is lucrative, with farmers easily making double the revenue on 100 pounds of organic milk.

Since the 1980s, the Hass family has been with La Farge, Wisconsin-based Organic Valley, a cooperative that roots its ethos in the sustainability of small towns.

“When the family farms fail, the main street businesses start to fail, the school systems start to fail,” said Jeff Frank, Organic Valley’s CEO. “There’s a direct tie (from farming) to health of rural communities.”

But not every farmer has bought into that messaging. Equally alluring are the economies of scale, which prioritize doubling, even tripling the number of milking cows on feed.

A USDA economist’s 2020 report found as farmers grew their herd size from, say, under 50 cows to more than 200 cows, they saw the cost to raise a hundredweight of dairy drop from more than $33 to just upward of $20.

Such math is hard to ignore. According to the latest agriculture census, in 2022, there were 775 dairies across Minnesota and Wisconsin with more than 500 cows. That’s triple the farms in that big category from just two decades earlier.

“There’s two efficiencies in dairy,” said Rick Alberts, a dairy farmer outside Pine Island, Minnesota, who attended Gov. Tim Walz’ visit to a local farm in July. “There’s profit-per-cow, and there’s efficiencies of scale.”

He detailed how the technology of a milking parlor can enable milking many more cows per hour.

Earlier this summer, news broke that Morris, Minnesota-based Riverview Dairy aimed to build a 25,000-cow operation north of Fargo in Hillsboro, North Dakota. And South Dakota’s dairy cow population exploded by 70% since 2019, with large operations going up along Interstate-29.

Meanwhile, up and down the spine of the Mississippi River, the symbiotic relationship between dairy farms and small towns appears to be fraying.

Last November in Winona County, a judge upheld the county’s decision to cap a family-owned dairy from expanding much beyond 1,000 cows. In Wisconsin east of the St. Croix River, citizen groups have had less success protesting dairy expansions, some proposing more than 5,000 cows.

At a meeting of the Wisconsin National Resources Board in Turtle Lake, former Emerald, Wis., resident Kim Dupre said officials turn the other way when manure from concentrated animal feedlots drives up harmful nitrates in private wells.

“What are rural residents supposed to do?” Dupre asked during public comment. “The disparity of access to safe drinking water was striking, to me, between rural and urban, suburban Wisconsin.”

A University of Minnesota report said the average dairy farm generates $1.6 million in economic activity. But growing sentiment undercuts the mantra that rural America must rise and fall with agriculture.

“Agriculture was the primary industry early in the development of this country,” said Benjamin Winchester, a rural sociologist with the University of Minnesota Extension, who rejects the notion of agriculture in the driver’s seat of rural America. “Today, 95 percent of rural people are not engaged in ag or an ag-related field.”

Still, down dirt roads and past sloped barns, a narrative linking the farm and main street is hard to shake in certain corners of rural America. Of the top 10 counties for dairy production in Minnesota, three (Winona, Wabasha and Stevens) lost population between 2000 and 2020 but grew their number of cows.

Such trends could have far-reaching ramifications, from economic stimulus to even national security. In January, USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack decried rural population declines, noting a “disproportionate number” of veterans “come from these (rural) communities.”

A counter to this trend appears to be a small, but hopeful opening for organic farmers.

Earlier this year, Organic Valley announced 100 new farmers — hailing from Pennsylvania and New York to Indiana and Kentucky — added to its membership rolls. For the Hass family, who joined the cooperative in its inaugural year of 1988, the organic option was also a simple math problem.

“We did it — organic — since the ’70s,” said Al Hass, Lisa Hass’ husband. “We just never got paid that way.”

The Hass farm rises from a narrow road that feels like a voyage into farming’s past. An Amish neighbor keeps a wagon stored on the front lawn. On the soaring paddocks, woods and waterways all around, the Hass’ rainbow herd roams.

After school, the Hass’ teenage grandson helps with chores around the farm. Their daughter, Tammy Hass, manages the herd. Even in this idyllic environment, though, the family knows economic headwinds blow across dairy-land.

In January, French food giant Danone sold its struggling organic holdings, including the popular Horizon Organic brand, to a Beverly Hills-based private equity firm. Organic acres continue to decrease across the U.S. And earlier this summer, George Siemon, Organic Valley’s co-founder and CEO until 2019, told Lancaster Farming “the market’s gone flat” in organics.

Still, in Organic Valley’s corporate, small-town offices and on newly enrolled farms, there’s optimism. Co-op staff know the infamous market research study the New York Times has quoted showing Gen Z consuming 20% less fluid milk than the national average in 2022. But that doesn’t account for the increasing popularity of cheese and butter.

“If you look at dairy as a whole,” Frank said, “there’s a lot of bright spots.”

They also are still growing their farm. The Hass family actually left dairy farming a couple decades ago for a variety of reasons, but after about a 10-year hiatus, they returned the cows to the farm. The stability the organic market offered provided the family with a way back into the industry, with Lisa Hass noting the price for conventional dairy farmers remains roughly what the farm had received in 1988.

“Conventional has that fluctuation,” Lisa Hass said. “We know what we’re going to get. So we’re pretty blessed to do organic.”