Gathered in a senior center cafeteria on a hot July evening earlier this summer, a dozen Lewistown residents took part in a ritual that has become as much a tradition of the American West as rodeos and Fourth of July parades: debating the merits of a housing development before their City Commission.

The proposal: A four-story, 24-unit apartment building on a long-vacant hillside four blocks from Main Street, pitched by an out-of-town developer seeking a zoning change that would allow a monolithic building rather than a row of mobile homes.

The opposition: A succession of local residents, including neighbors who’d prefer not to have a new development looming over their backyards, voicing concerns ranging from traffic to stormwater runoff.

“I know Lewistown has to grow, I know Lewistown needs to provide more housing. There’s no question about that. I understand that,” said one neighbor, Perry Howell. “But I would just hope we do a real thoughtful process and try to make sure we check all the boxes before we just slam something in there.”

People are also reading…

Dozens, if not hundreds, of public debates much like this one have played out across Montana in recent years over subdivisions in Whitefish, trailer park redevelopment in Great Falls, and mid-rise apartment complexes in Bozeman, among many others. They’ve acquired a particular urgency — and particular angst — since COVID-era migration swamped many parts of the state with new arrivals, producing bidding wars that have driven up rents and home prices to levels unaffordable to many existing residents. As those debates play out in meeting rooms across the state, they’re gradually deciding the development patterns that will shape Montana for decades to come.

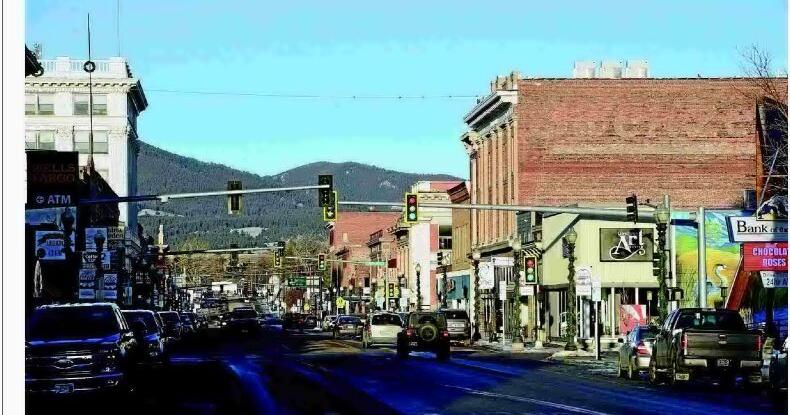

Lewistown, a small city smack dab in the center of Montana, was until recently sheltered from many of the winds that have driven the flames of landuse debates in other communities. Instead, like many agriculture-centric rural communities, it has spent decades in a state of steady demographic decline, a trend driven in part by the gradual consolidation of local farms and ranches.

The city’s population peaked in the early 1960s, as the U.S. Air Force’s Cold War efforts to install nuclear missile silos across central Montana brought a wave of workers to the area. Lewistown’s population, measured at about 7,400 in 1960, had slipped to about 5,800 by the year 2000. But it has begun to rebound in recent years, reaching an estimated 6,149 last year.

Lewistown today shows visible signs that modest population growth has come with renewed vibrancy. A few new chain businesses, including a Town & Country grocery store, have opened their doors in recent years, many setting up shop in new buildings along the highways running in and out of town. Main Street still has some vacant storefronts, but also cozy coffee shops, a bustling brewery and parks connecting to a citywide trail network.

Last year’s announcement that German industrial technology company VACOM will site a major campus in Lewistown, adding as many as 200 local jobs in the coming years, appears likely to fan those economic embers to a crackling flame. A long-planned effort to update aging nuclear missile silos across central Montana could also bring as many as 3,000 temporary workers to the area in the coming decade. Growth is on the horizon here.

Inevitably, that prospect spurs mixed feelings for many residents — especially given how new arrivals, out-of-state money and booming development have transformed other parts of Montana.

This story was reported in collaboration with the Lewistown News-Argus newsroom as part of Montana Free Press’ 2024 reporter residency program, which places MTFP reporters for weeklong stints in community newsrooms throughout the state. Special thanks to News-Argus staffers Will Briggs and Deb Hill their insights.

A community survey commissioned by city government last year drew more than 300 responses, many articulating optimism about the opportunities that growth could create: more shopping options, restaurants with longer hours, perhaps money for a dog park. It also captured explicit fear about what has happened elsewhere in regards to housing affordability and culture change, with many respondents citing certain fast-growing Montana cities by name.

“I’m afraid of it turning into the next Whitefish or Bozeman. Housing and land being so expensive that it drives people out,” wrote one unnamed resident.

“Having worked in construction in Bozeman at the beginning of the housing boom my main worry is that it turns into what that has become,” wrote another. “There is subdivision after subdivision of cookie cutter houses with privacy fences that don’t foster communities. Many of the subdivisions are built on some of the best farm ground in the state and even with all the new houses the prices are still going up.”

Located hours from the nearest major cities, Great Falls and Billings, Lewistown hasn’t faced the forces that have whipped up growth in Bozeman — among them Montana State University, easy access to a regional airport, and proximity to the tourism destinations of Big Sky and Yellowstone National Park. As such, Lewistown leaders may have an easier time navigating their community toward a Goldilocks future that’s neither too hot nor too cold.

City and county officials interviewed by Montana Free Press in recent weeks acknowledged that task. They said they’re working on a variety of efforts to effectively accommodate growth, ranging from nitty-gritty landuse planning to pondering broader social issues such as how to integrate new arrivals into the community’s social fabric.

Fergus County Commissioner Ross Butcher said he’s hopeful that the VACOM development will bring new arrivals who are enthusiastic about becoming involved in community affairs, as opposed to remote workers who he said are sometimes less engaged.

“We need baseball coaches and swim instructors and people that are going to join the Kiwanis — that’s what we need, is we need community members,” he said.

Butcher also said he thinks existing residents have a responsibility to be welcoming.

“If you don’t reach out and befriend and network with the new folks that are moving to your town, they’re going to start developing their own cultures off to the side. And if you really want to maintain what you think makes your community what it is, then you need to bring them in and help them become part of that culture,” he said.

Butcher and city leaders said they’re pondering more tangible aspects of growth too — where it does and doesn’t make sense to encourage new housing and commercial development, and where to spend limited public dollars extending costly streets and sewer lines.

City leaders say they’re banking on an ongoing effort to update Lewistown’s growth policy, the formal document that guides city land-use decisions, for the first time since 2006. They hope that planning effort, being conducted under a newly modernized set of state land-use statutes, will give the city and surrounding areas a roadmap for navigating the growth ahead.

Population projections prepared as part of that update indicate Lewistown proper could grow to just shy of 8,000 people by 2030, an estimate that includes 700 VACOM workers and family members. Housing that growth would require about 4,100 homes of varying sizes — about 720 more than the city’s current stock.

Lewistown city planner Doug Osterman said developers are already working on between 300 and 400 new housing units inside city limits, including the proposed hillside apartment building and a major redevelopment of a former sawmill site. He said he’s hopeful the additional supply will be enough to keep home prices from spiraling through the roof as new workers move into town.

Osterman’s preferred approach to meeting Lewistown’s need for additional housing is to encourage urban-density development inside city limits, as opposed to far-flung subdivisions on surrounding fields. In addition to preserving farmland and other open space, that approach would let new housing developments minimize their construction costs by piggybacking on existing city infrastructure.

He also said he’s been encouraging developers to consider duplex-style development that can be built at more affordable price points than standalone homes.

“We’re trying to do this in a way that does increase density, but does it in a good way and does result in a range of affordability as well,” Osterman said.

Even if Osterman and other Lewistown officials can articulate a clear vision for healthy growth — and sell the public on it — translating that vision into bricks and mortar will remain a significant leadership challenge. The trajectory of development in the Bozeman area, for example, has resulted in widespread public frustration despite the existence of a series of lengthy municipal growth plans required by state law, the most recent of which was adopted in 2020.

Public land-use planning is a perennial sore spot in Montana, where planning efforts must withstand both Montanans’ traditional distaste for government intrusion on private property rights and pressure from growth-skeptic residents.

Local government leaders must also contend with the reality that they’re almost entirely reliant on the private sector to implement key parts of any plan they put on paper, particularly in regards to housing. Outside of scattered nonprofit efforts and a few taxpayer-subsidized projects built each year through the Montana Board of Housing, nearly all new housing built in Montana is driven by private sector developers who pull the trigger only when they believe they can turn a profit. Land-use law often gives city and county officials the power to block development proposals, but it doesn’t give them the power to conjure projects from thin air.

The result in Lewistown, Bozeman and beyond is that when push comes to shove, land-use policy in Montana is often implemented piecemeal, as individual projects like Lewistown’s hillside apartment building are subjected, for better or worse, to the unpredictable passions of community politics.

“When you get down to public hearings, all bets are off, and the right sophisticated people can stop anything in its tracks — or at least delay it until it’s not feasible anymore,” said Osterman, the city planner.

In an interview shortly before the July meeting, Lewistown City Commission Chair KellyAnne Terry said she was unsure whether the apartment project, which she supports, was going to get the votes necessary to pass its zoning change. (It ultimately did.)

Terry said she feels for longtime residents who don’t want their neighborhoods to change, but also feels obligated to weigh that concern against a pressing need for more homes.

“It’s very hard to turn down a developer when we’re in such a housing crisis,” she said.

The way local government leaders manage the approval of housing developments has come under scrutiny in recent years in Montana and nationally, with policymakers as prominent as President Joe Biden’s White House arguing that many cities have made their communities less affordable by siding too often with anti-development homeowners. Last year, the Republican-controlled Montana Legislature passed a slew of laws that limit city zoning powers in an effort to promote housing development.

The Legislature also passed a major update to the state’s land-use planning law that aims to make planning efforts more effective. The new approach is required for most cities in urban counties but optional for rural communities like Lewistown, where the City Commission voted to use the new rules earlier this year.

The new approach will try to shift how the public participates in land-use planning, discouraging debates over specific proposals by putting most decisions in the hands of administrative staff, rather than the votes of elected officials during public meetings. Specifically, once an updated city zoning map is adopted under the new statute, proposals that are in “substantial compliance” with it will in most cases be subject only to administrative review — unless objecting parties request an appeal.

Advocates for the change say it will make growth plans a more certain template for the future by ensuring they aren’t derailed by not-inmy-backyard political pressure. Opponents, including a Bozeman-based homeowners’ coalition that is challenging the law in court, have argued the change unjustly cuts the public out of the loop.

In theory, residents in growing communities like Lewistown will instead have their chance to participate in land-use debates earlier in the process, while new zoning maps are being drafted. To that end, the city has circulated the community survey and held a series of open houses and public meetings as its planning commission hammers out the details of its new policy, which should be finished in early fall.

Tim Robertson, a planning commissioner who also sits on the full City Commission, acknowledged in an interview that development will inevitably be driven by market forces beyond city leaders’ full control. But, he said, he also saw firsthand what happened when Williston, North Dakota, was overwhelmed during the Bakken oil boom of the late 2000s and early 2010s. Robertson hopes the city’s new growth plan can help avoid that chaotic trajectory.

“It’s forcing us as a community to look at how things might develop and how we might want to influence the natural course of things,” he said.

But Robertson said he’s confident there will be bumps in the road regardless.