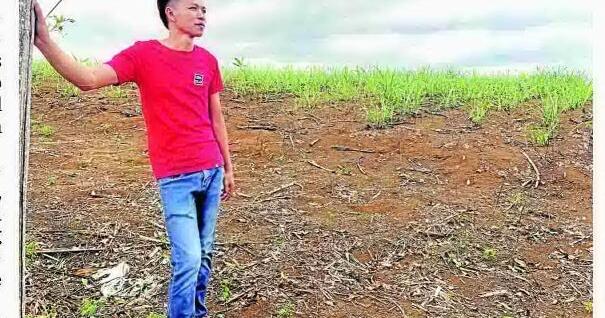

MINDANAO, Philippines — Joemar Flores, a spindly 28-year-old, gestured across his family’s farmland, nestled between a steep hill and a river, and expressed gratitude for the rice paddies in the distance.

They’re still there, producing food and an income for him, thanks in part to a novel form of insurance increasingly being used to help vulnerable populations build resilience to climate change.

Back in 2022, the young father of a toddler and a newborn faced ruin when heavy rains and violent winds decimated his rice crop.

“We were very discouraged,” he recalled, as he pointed to a photo of the destroyed paddies.

Flores borrowed 30,000 Philippine pesos — a little more than $500 at today’s exchange rates — to purchase the rice seedlings and fertilizer he needed for the crops that provide his family’s livelihood. Without the harvest, he wouldn’t be able to pay back the loan or have any money to replant.

People are also reading…

Luckily for Flores, the local cooperative where he borrowed the money had an emergency fund bolstered by the experimental insurance. The co-op was able to forgive part of the loan and extend Flores another one, which allowed him to replant.

Typically, insurance payouts after a disaster are based on actual damages determined by an on-site inspection by an assessor. This usually involves a lot of paperwork, bureaucracy, and waiting — sometimes for years.

But Flores’ co-op has a unique insurance policy: a Luxembourg-based company working with a local Philippines-based insurer pays policyholders based solely on the amount of rainfall and wind speed in a defined area, as measured by satellites. The policies are designed to protect against flooding, drought, and typhoons, as well as heat waves.

No damage assessment or site visit is required. The payments are based purely on predetermined statistical thresholds that, when met, trigger an automatic payment. These mechanical triggers, or parameters, give the insurance product its moniker, “parametric insurance.”

Recipients of the payouts, in this case the co-op, are notified in days and money is deposited directly into the co-op’s bank accounts within a week or two. The rapid payments get rebuilding underway quickly after disasters.

The quick, straightforward payouts of these policies could encourage the use of insurance in vulnerable areas that long lacked coverage, especially emerging markets, says Arup Kumar Chatterjee of the Asian Development Bank, which has overseen several pilot projects in the region. “It’s a good solution,” he said.

Parametric insurance isn’t perfect and can’t provide complete protection.

Co-ops say covering a full range of contingencies is too expensive, and the satellite-based payouts sometimes don’t directly correlate with actual damage on the ground. That’s why Flores’ co-op has an emergency fund; if the co-op gets an insurance payout that its members don’t need, the money gets saved for the next time its members need financial support, and the co-op might not receive a payout.

Though not a new concept, parametric insurance took off with advances in satellite weather monitoring and computerized data processing. That made it easier to deploy widely and inexpensively in hard-to-access communities. These policies spread risk, like traditional insurance, but sidestep many of the overhead costs and time needed to assess actual damage.

They have been used in developed countries, such as the U.S. and Europe. Advocates hope the novel approach to disaster coverage — part of a wider rethinking of the global insurance industry in the face of climate change — will especially improve insurance coverage in poorer, remote areas that are especially vulnerable.

“We really want to make sure that our farmers are not left behind,” said Noel Raboy, president of CLIMBS, a Philippines-based insurer that underwrites and sells parametric policies, including to Flores’ co-op.

The policies are often being used in novel ways. They can be used to help address new varieties of risks associated with climate change that are difficult to insure against — such as loss of income from heat stress.

In India, they were paired with workplace guidelines that shut down assembly lines when temperatures rise above safe levels. The insurance partially covered payments to day laborers who otherwise would have lost all their income for that day.

In Bangladesh, they covered crop damage from seawater intruding into fields, based on automated soil humidity measurements taken remotely.

About $13 billion worth of parametric insurance policies were written last year worldwide, a figure that could surpass $29 billion by 2031, according to Allied Market research.

The Philippines is developing a plan with the Asian Development Bank to deploy parametric insurance for 10 cities across the country. If that program works, the hope is that it can be expanded.

The CLIMBS insurance cooperative, based in the city of Cagayan de Oro on the island of Mindanao, began working with Luxembourg-based IBISA to design parametric insurance for its mostly rural member cooperatives about four years ago.

The product, launched in 2021 with 14 cooperatives representing about 3,600 farmers in 15 provinces, now is being deployed by 126 cooperatives covering the loans of more than 85,000 farmers in 61 of the Philippines’ 82 provinces.

This story is a collaboration between Cipher News and The associated Press.