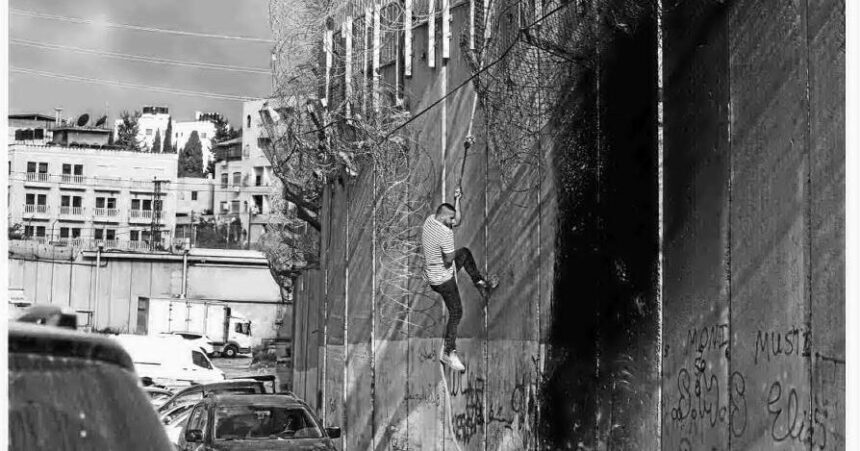

YATTA, West Bank — In mid-May, Sayyed Ayyed and several other unemployed Palestinian men gathered near the towering wall of concrete and barbed wire separating the occupied West Bank from Israel at dawn.

A smuggler was present with a ladder and ropes. Each man paid around $100. Ayyed waited his turn while others climbed over.

The 30-year-old father of two daughters had been out of work for a year. He had mounting debts and rent to pay. On the Israeli side, there was the promise of work at a construction site. He just needed to get over the wall.

“When you see that your children have no food,” he said, “the barrier of fear disappears.”

A year of conflict in Gaza has had repercussions in the West Bank, where the economy is in danger of collapse due to Israeli restrictions preventing Palestinian workers from entering Israel for work, along with a surge in violence.

People are also reading…

Unemployment has risen drastically to 30%, from about 12% before the conflict. In the past year, approximately 300,000 Palestinians in the West Bank, many of whom worked in Israel, have lost their jobs, according to the Palestinian Economy Ministry. The territory’s economy shrank by 25% in the first quarter of 2024, as reported by the World Bank.

Desperate for work, some Palestinians are resorting to smuggling themselves at great risk through the guarded barrier into Israel.

When they manage to find work, Israeli security forces either arrest them or, in some cases, open fire. There are no official figures from Palestinian authorities on workers killed or injured by Israeli gunfire while attempting to cross the barrier. The families of three Palestinians told the Associated Press that their relatives were killed in the attempt.

“These people are being shot at while trying to go to work,” said Assaf Adiv, director of MAAN, a worker’s association focusing on Palestinian labor rights.

Previously, around 150,000 Palestinians from the West Bank legally crossed into Israel daily for work, primarily in construction, manufacturing, and agriculture.

After Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, Israeli authorities prohibited most Palestinians from entering, citing security reasons. Tens of thousands of Palestinians were suddenly left without jobs.

Eyad al-Najjar, a 47-year-old laborer from a village near Yatta in the West Bank, entered Israel through a barbed-wire section of the barrier in July, earning about $650 for a week’s work, according to his family.

But then his son got married, putting the family in debt. So al-Najjar tried his luck again.

He approached a hole in the barrier on Aug. 26, three days after the wedding. Israeli troops saw him and shot him, killing him with a headshot, his relatives said.

“His children will have to work to pay off this debt in the future,” said relative Jawadat al-Najjar. “No one helps in these difficult times.”

The Israeli military declined to comment on the shooting without specific location details provided by the relatives.

Many Palestinians have seen their means of living destroyed by the restrictions. Some have sold belongings. Children on West Bank roadsides sell items like tissues, bottled water, and air fresheners. Some men have resorted to selling sandwiches at makeshift stalls.

It’s not just the loss of jobs in Israel. The military has also tightened its control in the West Bank, setting up new military checkpoints that hinder the movement of goods and workers.

Vehicles can wait for hours as soldiers conduct inspections, whereas before the conflict, many were allowed to pass through quickly. Some roads are completely closed off. In one instance, a road connecting 12 villages to Dura in the south was closed by the army, according to local activist Badawi Jawaed. Many workers were unable to reach their jobs and were laid off, he said.

Violence has escalated, with increasing Israeli raids targeting armed groups. The Palestinian Health Ministry reports that over 700 West Bank Palestinians have been killed by Israeli gunfire. Many were killed in armed clashes, others for throwing stones at troops. However, some appeared to pose no immediate threat.

In Israel, Palestinians can earn double or triple what they would in the West Bank. The barrier, stretching about 400 miles and reaching a height of 23 feet, stands in their way.

The construction of the barrier began in 2002 following numerous suicide bombings and attacks by Palestinians from the territory that killed Israeli civilians during the second intifada.

Ayyed used to work for an Israeli construction company that paid $1,850 monthly. Without that job since the conflict started, he searched for work in his hometown of Jenin in the northern West Bank.

Ayyed tried grocery stores and restaurants but found no job opportunities.

To survive, he borrowed money from friends, accumulating around $1,600 in debt. He cut back on utilities. By spring, he had exhausted all borrowing options and had a $500 rent to pay each month.

So he took a risk.

As he climbed the wall, the ladder slipped, causing Ayyed to fall and break his leg on the West Bank side.

He returned home without a penny.