Lauren Cochrane, 34, perched at the head of a long wooden table, phone in hand, checking her workday schedule out loud. One meeting at 10:30 a.m., another at 11:30. A few feet away, her husband, Kyle, 39, compared her daily calendar to his own, mapping out overlapping obligations and strategizing time slots when he could watch their 11-month-old daughter, Sloane. Between them, Sloane lifted bits of orange and homemade bread to her mouth, juice and crumbs dribbling onto her green mealtime poncho.

“It’s going to be a busy day here,” Lauren said as Sloane babbled at her side.

Until December of last year, the Cochranes relied on a hired nanny to help care for Sloane and their 2-year-old son, Howie, during the work week, splitting the cost with another family. But that arrangement expired shortly after Christmas, and the Cochranes abruptly found themselves searching for other options. They secured a spot for Howie at the Alberton Early Learning Center, a half-hour drive from their home in the forested foothills above Frenchtown. Unable to find an open slot for Sloane, Lauren and Kyle spent the winter hosting guests, family and friends from out of town who could watch their daughter while they worked.

That situation, too, proved unsustainable. So the Cochranes made the tough choice to juggle childcare with their fully remote tech jobs, working together to provide for their family financially while ensuring their daughter is fed, cared for and entertained throughout the day.

“She’s just watching you work,” Lauren said. “But in my head sometimes it’s like, I should be on the floor playing with her, and I’m up here and she’s going to be like, ‘Mom’s a slave to the computer,’ you know?”

Across Montana and around the country, scores of families are struggling with a childcare crisis that is only getting worse. For some parents, the cost of such care is swallowing a significant share of their annual earnings — an average of $18,940 in 2023, equivalent to 28% of the state’s median household income, according to the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. For others, lengthy waiting lists or lack of local providers have made childcare unattainable at any cost. The health department estimates that Montana’s current childcare supply meets less than 45% of the statewide demand. Even if hurdles of affordability and access are overcome, parents can still struggle to find a program that fits their expectations of quality care.

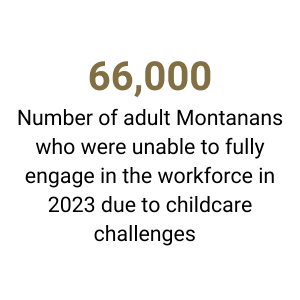

That mix of challenges kept an estimated 66,000 adult Montanans from fully engaging in the workforce in 2023, roughly 11% of the total civilian labor force reported by the Montana Department of Labor and Industry for the year. That’s one of several data points that have childcare advocates and higher education calling for statewide action to fix one of Montana’s biggest economic issues.

For Leigh Ann Courville, co-director of Salish Kootenai College’s Early Childhood Education Department, childcare seems to have gained particular public attention and policy interest in the wake of COVID-19. Pandemic-era school closures highlighted the state’s dependence on family support systems that many had previously taken for granted, reminding Montana that a healthy labor force needs a healthy early childhood infrastructure in order to thrive.

That reminder has helped usher childcare access and affordability to the center of recent state policy debates, but for campus leaders like Courville, the childcare crisis is hardly news. Responding to workforce needs is a major responsibility of higher education, and SKC has been trying to topple barriers for the next wave of workers in the Mission Valley for decades. It’s one reason the college leverages grant funds to ease the financial pressure on students, Courville said, and why her program developed a one-year track to entry-level certification in the childcare field.

“We need childcare so that people can work,” Courville said, noting that the need applies not just to private sector workers but to parents who return to college to improve their earning power. “It’s not just about women and children. It’s a community, it’s a state, it’s a national thing.”

About 50 miles north of the Cochranes’ home, Hayley Salois, 34, cradled a toddler on her hip as a pair of red-haired twins crawled across the tile floor on all fours and briefly vanished beneath a low table littered with lunchtime leftovers. They reemerged, hot on the heels of a rubber ball. Salois raised the toddler in her arms for a quick diaper sniff. The results, telegraphed by her slight nod, were negative.

“We need childcare so that people can work. It’s not just about women and children. It’s a community, it’s a state, it’s a national thing.”

Leigh Ann Courville, co-director, Early Childhood Education Department, Salish Kootenai College

Salois is one of about 67 students now working their way into the childcare field at Salish Kootenai College in Pablo, directly across the highway from the headquarters of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. She’s already halfway toward earning an associate degree in early childhood education, and plans to continue on to a bachelor’s degree.

Salois has also logged more than six months as a lead teacher in the infant-and-toddler room at SKC’s Early Learning Center, which is both a childcare provider and a training ground for the next generation of early education professionals.

Salois, who already has a paralegal associate degree, said she and her husband are intimately familiar with the childcare challenges facing families in her home state.

“I was a stay-at-home parent for so long just because childcare was so expensive. With five of my own children, there was no way that we could both work and send our children to daycare,” Salois said. She eventually returned to work as a family advocate for her community’s Head Start program, a federally funded education service offered free for children from birth to age 5, after her husband took a year off to care for their youngest child

Credit: John Stember

Despite her role recruiting and training a new generation of childcare workers like Salois, program leader Courville doesn’t shy away from the hard truth.

“Generally, early childhood [education] has been underfunded,” Courville said. “Our wages are not on parity with other professionals in comparison to public school systems. Yet more and more [childcare employers] want associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s-level degrees. But the salaries don’t always match that.”

Montana’s childcare system is beset by disparities. The majority of the state’s counties meet the national definition of childcare “deserts,” meaning licensed capacity meets less than a third of potential demand. The median wage for childcare workers in the state was $12.84 an hour in 2022 — about $2 less than the national median — and providers seldom offer employee benefits such as health insurance. The early childhood education profession can be a tough sell to prospective students, especially when it’s coupled with the rising price tag of a college degree.

Montana’s last-in-the-nation ranking for starting public school teacher salaries makes pivoting into a related career equally fraught.

“It’s a hard time to be a teacher,” said Allison Wilson, director of the Institute for Early Childhood Education at the University of Montana. “It’s a hard time to be a childcare provider.”

Wilson noted that Montana’s university system has divvied up programming for early childhood education, a discipline she and others in the field define as encompassing not just infants and toddlers but children in their first three years of elementary school. Wilson’s own program focuses primarily on pre-kindergarten through third grade, with college students earning state P-3 teacher certification along with a degree. Associate degrees and certifications related to younger ages tend to be found at smaller two- and four-year state campuses or tribal colleges, while the state’s other flagship, Montana State University in Bozeman, offers various degrees and provider trainings for both preschool and early elementary levels.

Wilson and others cautioned, however, that the workforce pipeline feeding the childcare system has historically not started within higher education. Entry-level provider positions don’t require a college degree, and even if such requirements did exist, Wilson stressed, the low wages endemic to the profession wouldn’t match the rising cost of attending college.

Absent some sort of public subsidy, Wilson said, she doesn’t see how the pipeline could be reconfigured to meet the workforce needs of childcare providers — at least not without saddling families with higher rates.

“The reason that works in K-12 education is because it’s publicly funded,” Wilson said. “The cost does not fall on parent[-paid] tuition.”

There are exceptions, of course. Missoula resident Amanda Wiseman, who this fall will begin pursuing her master’s degree in early childhood education under Wilson’s tutelage, started on the path as an undergraduate at UM-Western in Dillon. From there she landed a teaching job at a Missoula area preschool, and two years later advanced to directing the program.

But six months after giving birth to her and her husband’s first child, Wiseman came to the same decision so many other new parents have made: She quit her job.

“My whole paycheck was literally going into my pocket, then straight to [childcare],” said Wiseman, who made $16 an hour as program director. “So we decided I would just stay at home with him.”

Wiseman wasn’t alone. She spent those years with a coterie of stay-at-home mom friends who’d made similarly tough professional choices. But with her son approaching kindergarten and her 3-year-old daughter enrolled at UM’s early education lab school — a dual childcare provider/training facility similar to SKC’s early learning center — Wiseman said she’s ready for a more specialized course of study and a return to a career she’s long been passionate about.

Such career decisions require a balancing act — passion versus compensation — that Kelly Rosenleaf, executive director of the Missoula nonprofit Child Care Resources, said is damnably difficult for childcare workers to pull off.

“It’s emotionally and spiritually rewarding work,” Rosenleaf said. “But at the end of the day, you have to be able to feed your family, and you have to feel like you’re going to make it in retirement, and you’ve got to have health insurance. Those are just systemic problems because it does not pay enough. And yet parents are struggling to pay.”

Kyle Cochrane always wanted to live on the outskirts of his hometown. A Missoula native, he grew up on the banks of the Clark Fork, which flows just a few city blocks from his alma mater, Hellgate High School, on its way west to the rural foothills where he now lives with his family. He met Lauren a month after she moved to Missoula from Minnesota’s Twin Cities in 2018, and within a few years the couple found their dream home surrounded by trails and towering pines in nearby Frenchtown.

“It’s emotionally and spiritually rewarding work. But at the end of the day, you have to be able to feed your family, and you have to feel like you’re going to make it in retirement, and you’ve got to have health insurance.”

Kelly Rosenleaf, executive director, Child Care Resources

The Cochranes count themselves relatively lucky among their fellow Montanans struggling with childcare. They’re able to afford a nanny one day a week. And come August, there’s a good chance the early learning center in Alberton will have space for Sloane to join Howie. Those strokes of good fortune have given the Cochranes a degree of freedom and flexibility they understand many Montana families don’t have.

But their situation nonetheless exacts a personal and professional toll, and the abrupt loss of their nanny-share arrangement last year is evidenced by small but meaningful alterations in their work-from-home lives. Lauren has taken to stationing herself in the living room for portions of the day, standing with her laptop at a tall side table while Sloane plays on the carpet. Both parents have had virtual meetings interrupted by the calls of a child. They regularly eat lunch together with their daughter and make a point to take breaks for time outdoors with Sloane and the family’s two dogs. The Cochrane parents agree that there are pros to their reality, and there are cons.

“Raising two kids is hard,” Kyle said. “You add on any additional stressors, it’s amplified.”

One of the family’s most notable changes is their half-hour morning drive from Frenchtown down the Clark Fork to Alberton, where two-year-old Howie spends most weekdays on the second floor of a white house with green trim and a wide, wood-railed veranda. If all goes according to plan, Sloane will join her brother here starting in August — just as soon as Alberton Early Learning Center director and owner Felicity Day has the capacity to take her on.

Credit: John Stember

The Cochranes aren’t the only family holding out for an opening at the Alberton Early Learning Center. Day said she currently has eight families on her waiting list, and is still keeping three others in mind who recently withdrew from the list. Local interest “exploded fast” when she started the center two years ago, she said, a development she partly attributes to the fact that surrounding Mineral County has only two other registered providers with a combined capacity for 16 children.

Day enrolls up to 15 students, in line with state-mandated provider-to-child ratios. She’d love to increase that total, but that would require finding another employee with the knowledge and experience in early childhood development that she expects her program to deliver.

“That’s the hardest part for me,” Day said. “I can hire anyone off the street, right, to come and help. It’s people, it’s bodies, we need bodies to satisfy that ratio. But is it this? Can they do this? No. And that’s the problem that I am having.”